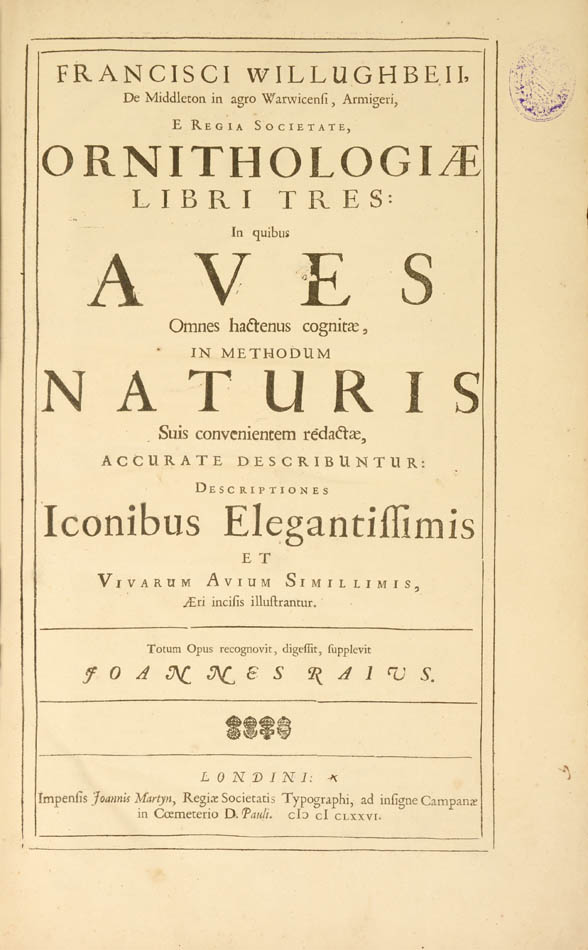

“”The Ornithologiæ libri tres (referred to as the Ornithology) is one of the first truly scientific ornithological texts. It was published four years after the death of Francis Willughby (1635–1672) by his friend and collaborator John Ray (1627–1705). These two natural historians had met at Trinity College Cambridge in the 1650s and spent time travelling around Britain and Europe collecting and observing nature.

Previous works concerning birds typically contained information gleaned from earlier sources such as Aristotle and Pliny with extra comments by the author. These works would usually describe the birds, where they might be found, whether they were edible, if they had any medicinal value, and what their human traits and characteristics were (for example Wrens are viewed as brave while Finches are dim-witted). It was also not uncommon to find mythical and fabled birds such as the phoenix and griffin amongst the pages of such works. As the study of natural history progressed the standards of ornithological works improved but they still lacked sensible and coherent organisation. Birds tended to be grouped together by habitat and then by their actions. Walter Charleton’s (1619–1707) system, explained in his Onomasticon zoicon (London, 1668), involved looking at the birds’ diets, whether they bathed (and in what water/sand) or sang. The way birds were ordered changed with the publication of the Ornithology. Firstly, they are classed here as land or water birds. The land birds are then divided into those with crooked beaks and claws and then those with straight beaks. The water birds are divided into those ‘that wade in the waters, or frequent watery places, but swim not; The second, such as are of a middle nature between swimmers and waders, or rather that partake of both kinds, some whereof are cloven-footed, and yet swim; others whole-footed, but yet very long-leg’d like the waders: The third is of whole-footed, or fin-toed Birds, that swim in the water’. This is thought to be the first attempt to rationally classify birds.

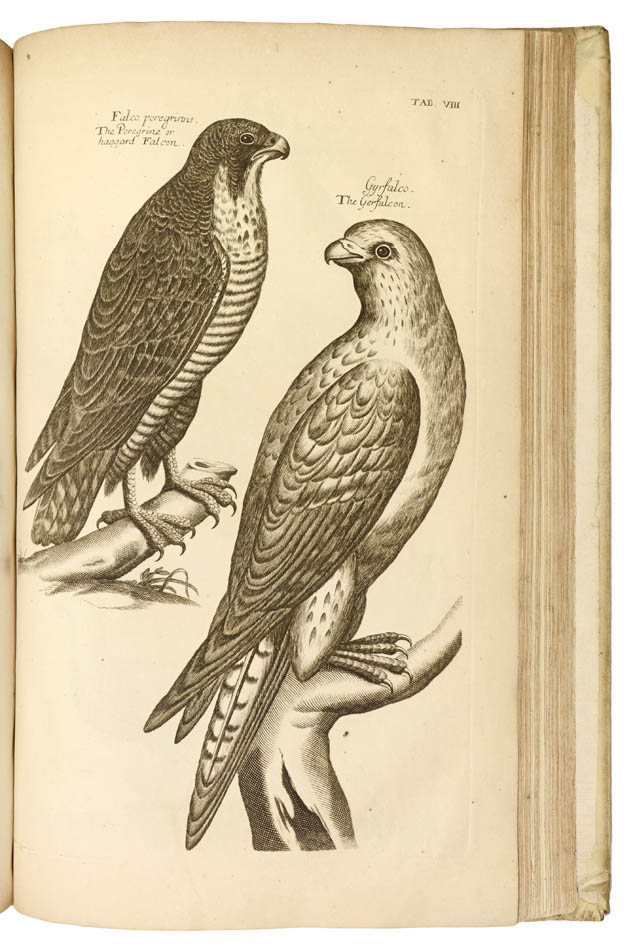

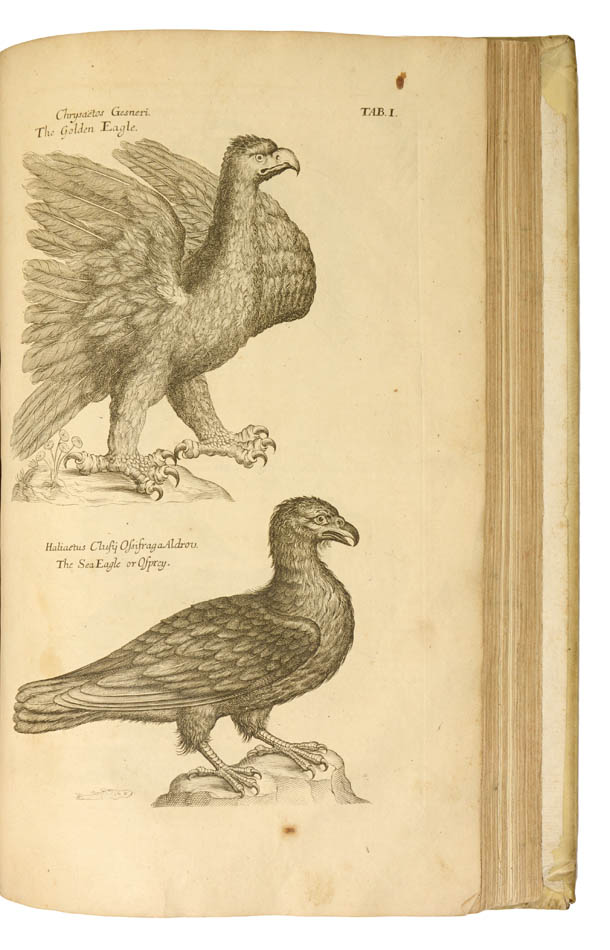

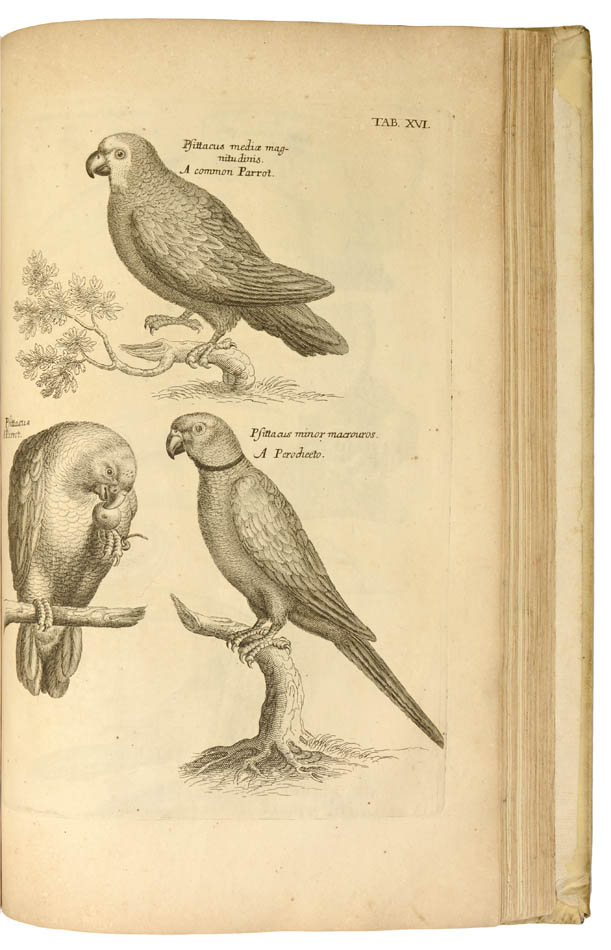

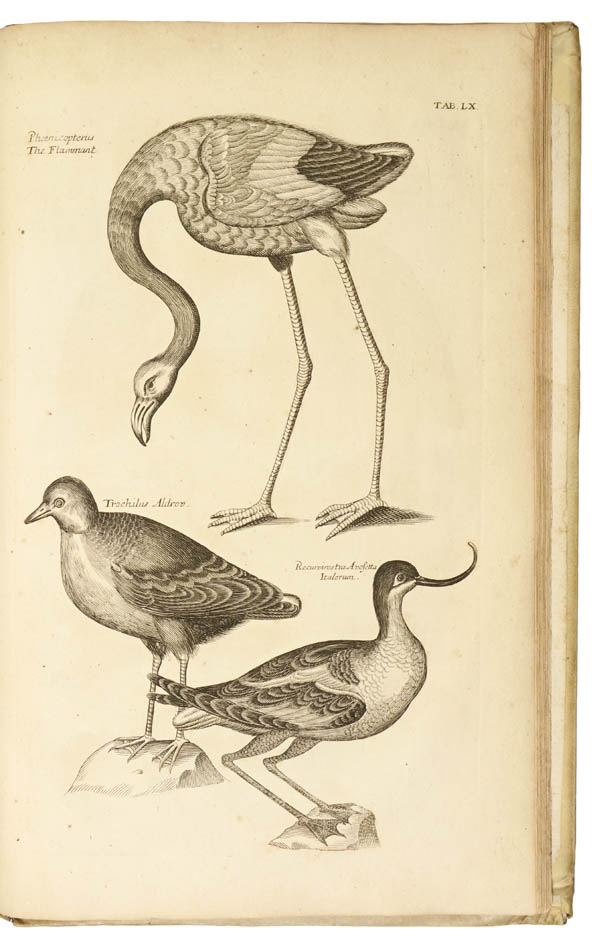

The 77 illustrations contained in the Ornithology come from various sources. Some are copies made from the collection of pictures and specimens owned by Willughby, others Ray had commissioned. The quality of the illustrations varies greatly; some are very lifelike and easily identified while others are not. Many of the birds have unusual postures for their species while those drawn from specimens (dead or alive) tend to be the more accurate. Ray himself puts the lack of quality down to the fact that he was unable to fully oversee the engravers’ work as he was away from London and had to send instructions by letter. The illustrations credited to Thomas Browne (1605–1682) are of the best quality. These are thought to include the illustrations of the Shearwater, Little Auk, Razorbill, and Great Northern Diver”” (Dawn Moutrey, University of Cambridge, Whipple Library).

Description

First edition. Folio (36.3 x 22.5 cm.), 2 folding letterpress tables, 77 engraved plates, lacking initial imprimatur leaf, browning to text leaves, title-leaf slightly frayed at fore-edge and with very small hole in centre, three plates with tears repaired, later vellum with arms tooled in blind on covers, a good example.

Provenance: Sacchetti, armorial bookplate and stamp on title-page.

Bibliography

Anker 532 (variant); Nissen IVB 991; Wing W2879 (with title-page variant recorded as ESTC R471002).